This guide sets out a general overview of the litigation process. It does not cover every possible stage of the process, but highlights those which are likely to apply to most cases.

As each case is different, the particular steps required, and timetable followed, will depend on the facts, circumstances and nature of the dispute. There are also factors that cannot be predicted in advance, such as actions taken by the defendant, evidence that emerges during the case, and directions or orders given by the court.

The overriding objective

One important principle that underpins litigation in English courts is the ‘overriding objective’ of enabling the court to deal with cases justly and at proportionate cost.

The key factors include:

- Enforcing compliance with the court rules and any court orders

- Dealing with a case in a way that is proportionate to the amount of money involved, importance of the case, and complexity of the issues

- Saving expense

- Ensuring that the case is dealt with expeditiously and fairly

These factors must be borne in mind at each step of the litigation process. When either the rules or a court order requires you to carry out a particular step in the proceedings, it is very important that you do so, in the manner stipulated, and within the relevant time limit. As part of its case management powers, the court may impose penalties on any party that does not comply with the court rules or orders. These penalties can include costs sanctions or striking out all or part of your evidence or claim.

Before you start a claim - pre-action protocols

- The courts will expect potential parties to act reasonably in exchanging information and documents relevant to the dispute before proceedings are even commenced. The aim is to avoid the need for legal proceedings where possible. There can be adverse costs consequences if a party fails to follow the relevant pre-action procedure.

- A claimant is ordinarily therefore required to send a "letter before claim" to a potential defendant, setting out the details of the claim, the remedy sought, and listing the key documents relevant to the dispute. It may include a request for documents or information from the defendant. The letter should also invite the defendant to agree to some form of alternative dispute resolution (ADR) procedure, such as mediation.

- A claimant should allow a defendant a reasonable time to respond to the letter before claim. This is usually in the region of 14 to 30 days, however, may be longer where required by an applicable Protocol. Depending on the defendant’s response and the position taken, it may be appropriate to issue proceedings, or to continue correspondence.

- The table below provides an overview of the standard pre-action protocol process that parties are encouraged to follow before court proceedings are commenced.

| Step | Completed by | Description of action | Timings and requirement |

|

Letter of claim |

Us on your behalf |

A detailed letter to the other side setting out:

|

Required. Should be sent as soon as possible. |

|

Letter of response |

The other side and/or their solicitor | The other side’s response to the claim and whether or not it is admitted |

Required. Should be sent within a reasonable period of time, usually 14 - 21 of receiving a letter of claim. |

|

Letter of settlement |

Either party |

A letter from either party (open or without prejudice) setting out:

|

There is no requirement for either party to make a proposal for settlement |

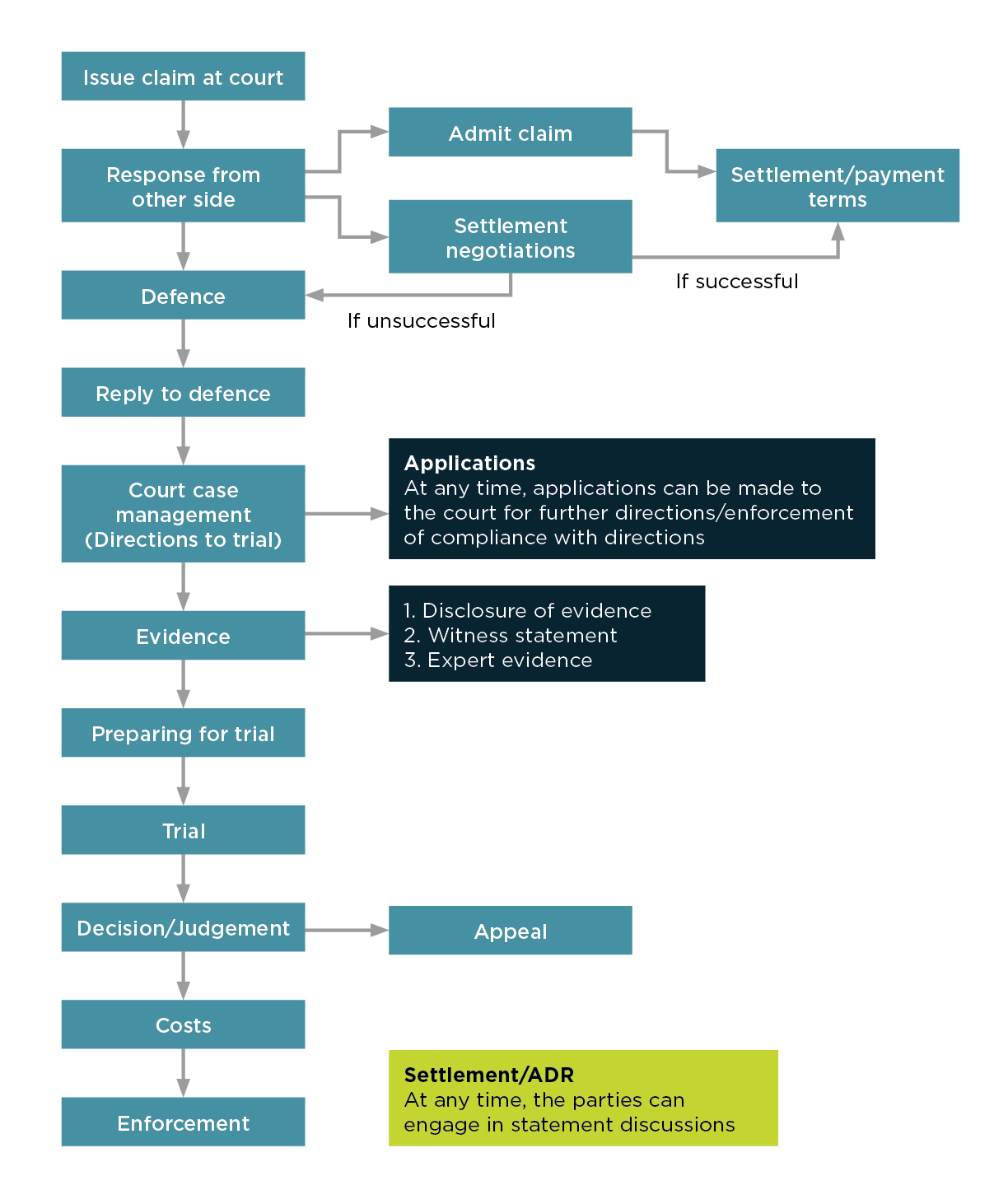

A typical process

If the required action involves issuing a claim at court, the typical process is set out below:

Preparing your claim for issue at Court

Statements of case

Each party to the proceedings must prepare certain documents that contain the details of the case they wish to advance. These documents (the statements of case) must be filed at court and served on the other party. The documents that comprise the statements of case are each dealt with below.

Claim form

Proceedings are started by issuing a claim form at court and paying the required court fee. The claim form contains a concise statement of the nature of the claim and the remedy sought (for example, damages). It must also include a statement of value of any money claim. A court fee is payable when issuing a claim and is calculated on the value of the claim being brought.

It is necessary to serve the claim form on the defendant within the prescribed time. The time limit is generally four months after the claim was issued, but, if it is necessary to serve the defendant outside England and Wales, we would have six months from the date of issue. It is our policy to take steps to serve the claim form as soon as possible after issue, unless there are good reasons to delay.

Particulars of claim

The particulars of claim set out full details of the claim, including the alleged facts on which the claim is based. The particulars of claim must be served on the defendant within 14 days of service of the claim form.

Statements of truth

Each statement of case must be verified by a statement of truth. This confirms that the person making the statement believes that the facts stated in the document are true. Statements of truth must also be signed in each witness statement and certain other documents filed in proceedings.

There are penalties for signing a statement of truth without an honest belief in the truth of the facts being verified. Further, a failure to verify a document can mean that the party will be unable to rely on the document as evidence of any of the matters set out in it, or that a statement of case is struck out.

Use of counsel

In some cases it is appropriate to instruct an independent barrister or counsel at an early stage. Counsel can give a second opinion on the merits of the claim, help with preparing the statement of case, and represent you at court hearings.

Response from the other side

Acknowledgement of service

The defendant must file an acknowledgement of service within 14 days of service of the particulars of claim. In the acknowledgement of service, the defendant must indicate whether he intends to defend all or part of the claim. He may also indicate whether he intends to contest the court's jurisdiction to hear the claim.

Defence

Unless the defendant admits the whole of the claim, he must file a defence. In the defence, the defendant must state which allegations in the particulars of claim he admits, which he denies and which are neither admitted nor denied but he requires the claimant to prove. Where the defendant denies an allegation, he must state reasons for the denial and put forward his own version of events.

The defendant must file a defence either:

- Within 14 days after service of the particulars of claim, if an acknowledgement of service has not been filed.

- Within 28 days after service of the particulars of claim, if an acknowledgement of service has been filed.

The parties may agree an extension of time of up to an additional 28 days for filing the defence. If the defendant wants more time, he will need to apply to court for a longer extension.

If a defence is not filed, you can apply to the court for judgment in default of defence.

Counterclaims and additional claims

Depending on the factual circumstances, the defendant may make a counterclaim against the claimant, or an additional claim against another party to the claim or a third party. For example, he may make a claim for a contribution or indemnity from another party.

A counterclaim or an additional claim may be served with the defence without the court's permission, or at any other time with the court's permission.

Reply to defendant’s case

As a claimant, you may file a reply to the defence, but you are not obliged to do so. You will not be taken to have admitted any matter raised in the defence if you fail to deal with it in a reply; you will be taken to require that matter to be proved by the defendant.

If a counterclaim is served, you should normally file a defence to the counterclaim within 14 days of service of the counterclaim.

Subsequent statements of case

In principle, it is then possible for there to be further statements of case, such as a reply to the defence to counterclaim. In addition, a party may seek to amend its claim or defence, although it is likely to require the court's permission to do so.

Interim remedies

Interim applications and final judgments without a trial

There are certain procedures that might enable us to obtain a remedy or judgment against the defendant before a trial. In some circumstances, this might avoid the need for a trial altogether. It is too early to advise on whether any of these procedures will be appropriate in this case. However, it is worth bearing in mind that these remedies might be available to you and, in some cases, the defendant. Some examples of interim remedies are mentioned below.

An interim application is made when a party seeks an order or directions before the trial or substantive hearing of the claim. An application may be made for a variety of procedural or tactical reasons, depending on the circumstances (for example, to seek an interim injunction, specific disclosure of documents or an extension of time to complete a procedural step).

We will advise you as the case progresses if any interim applications might be appropriate. If the other side makes any interim applications, it will be necessary to incur some additional time and cost in responding to them. Any costs orders that the court makes in relation to an interim application may have to be paid during the course of the proceedings.

Default judgment

If the defendant fails to file a defence within the relevant time limit, you may obtain a judgment in default of defence, which means that judgment is entered on the claim without a trial. In certain circumstances, the defendant may apply to the court to set aside default judgment and for permission to file a defence where the defendant can satisfy the court that it is appropriate to do so.

Summary judgment

Summary judgment is a means of obtaining judgment against the defendant at an early stage, avoiding the need to pursue the claim to trial. It may be appropriate to apply to court for summary judgment, either on the whole of the claim or on a particular issue, if it can be established that:

- The defence has no real prospect of succeeding.

- There is no other compelling reason why the claim or issue should be disposed of at a trial.

Note that summary judgment may also be sought by a defendant, on the grounds that there is no real prospect of the claim succeeding.

Striking out

The court has the power to strike out a party's statement of case (including a claim form, particulars of claim or defence), either in whole or in part, if one of the following applies:

- The statement of case discloses no reasonable grounds for bringing or defending the claim.

- The statement of case is an abuse of process.

- There has been a failure to comply with a rule or court order.

Security for costs

The defendant might seek an order that you provide security for his costs of the proceedings, for example, by paying a sum of money into court. The court will only make an order if it is satisfied that it is just to do so in all the circumstances of the case. The rationale for this measure is to offset any possible injustice to a defendant who may otherwise be unable to recover his costs of defending a claim against him.

Interim injunctions

An injunction is an order that requires a party to do, or to refrain from doing, a specific act or acts. For example, a freezing injunction could be sought to preserve the defendant's assets pending judgment or final order, if there is a risk that the defendant will dispose of assets that would otherwise be available to meet his liability.

An application for injunctive relief is not a step that should be taken lightly. A claimant is usually required to give an undertaking in damages, that is, an undertaking to compensate the defendant for any loss incurred, should it later transpire that the injunction was wrongly granted. Should it appear that it would be appropriate to seek an injunction, we will advise you in more detail.

Case management by the Court (directions to trial)

After a defence has been filed, the court will serve a notice of proposed allocation to the small claims track, fast track or multitrack. Where the claim is allocated to the fast or multitrack, the notice of proposed allocation will require the parties, by the specified date, to:

- Complete, file and serve a Directions Questionnaire.

- File proposed directions.

- Comply with any other matters.

Directions questionnaire

The aim of the directions questionnaire is to provide information to assist the court in allocating the case to the appropriate track and in giving directions for how the case should be conducted. In the directions questionnaire, you must set out your proposals in relation to the following:

- Disclosure of documents.

- Scope and extent of disclosure of electronic documents.

- Expert evidence that will be required.

- Witness evidence that will be relied on.

- Directions, that is, the procedural timetable for the matter.

- Possible settlement, or reasons why they do not wish to settle at that stage.

Each party must also file a budget of his costs for each stage of the litigation including trial.

The directions questionnaire must be filed by the date specified in the court's notice of proposed allocation. Therefore, it is necessary to address each of these issues at an early stage in the proceedings.

Case management conference

A case management conference (CMC) or costs and case management conference (CCMC) is a procedural hearing where the court gives directions for the future conduct of the case until trial. There may not be a CMC if the parties have agreed directions, or the court issues its own directions, and there is no other reason to have a hearing.

If a CMC is held, the court will usually:

- Consider the issues in dispute and whether they can be narrowed before trial.

- Consider the suitability of the case for settlement.

- Set a pre-trial timetable for the procedural steps required, such as the disclosure of documents, exchange of witness statements and expert reports.

- Fix a trial date or period in which the trial is to take place.

The court may order that a further CMC be held, particularly in complex cases.

Evidence

To succeed in litigation, a claimant must prove his case on a balance of probabilities. It is necessary to adduce evidence to support each of the essential ingredients of your claim. The defendant will also need to adduce evidence to support his defence to some or all of the essential ingredients of the claim.

The evidence is usually comprised of:

- Contemporaneous documents (including electronic documents as well as hard copies) intended to prove the issues in dispute.

- Statements of factual witnesses, to tell the story behind the dispute and to fill in any gaps that the documents leave.

- Expert evidence (where appropriate and permitted), to assist the court when the case involves complex technical, academic or foreign law issues.

It is important to consider, at an early stage, the evidence that is likely to be required to prove your case to enable us to prepare for the first CMC as discussed above.

Disclosure of documents

The purpose of disclosure is for each party to make available documents which either support or undermine any party's case. This may include documents that are harmful, sensitive or confidential. Disclosure is often a time-consuming and costly stage in litigation.

Initially, it will be necessary to identify:

- What documents exist (or may exist) that are or may be relevant to the matters in issue in the case.

- Where and with whom those documents are or may be located.

- The estimated cost of searching for and disclosing them.

The most important point to note at this stage is to preserve all documents that are potentially disclosable, including electronic documents such as emails, voicemails and text messages. Care should also be taken to avoid creating any document that might damage your case, and to limit the circulation of existing documents relating to the dispute.

Privilege

Privilege entitles a party to withhold documents from inspection. In particular:

- Legal advice privilege protects confidential communications between a client and his lawyer that came into existence for the purpose of giving or receiving legal advice.

- Litigation privilege arises when litigation is contemplated, pending or in existence, and protects communications between a client or his lawyer and a third party, provided certain criteria are satisfied.

- Without prejudice privilege applies to communications made in a genuine attempt to settle a dispute.

Witness statements

It would be helpful to identify those individuals who were involved in the events giving rise to the claim. If the claim proceeds, it will be necessary to prepare a written statement of the evidence that each individual intends to give to support the claim. These statements will be sent to the defendant, who will prepare and serve his own statements.

The time period for exchanging witness statements will be agreed by the parties or ordered by the court at the first CMC. The court may also give directions identifying the witnesses who may give evidence, or limiting the number of witnesses and the issues that may be addressed.

A witness statement must:

- Be in the witness's own words, if practicable.

- Indicate which of the statements in it are made from the witness's own knowledge and which are matters of information or belief and state the source of those matters.

- Include a statement of truth.

A witness may be called to trial to be cross-examined on his statement.

Expert evidence

Expert evidence is used where the case involves matters on which the court does not have the requisite technical or academic knowledge, or the case involves issues of foreign law. We will advise you if we consider expert evidence is required in your case.

The court's permission to call expert evidence is always required. If it grants permission, the court will limit the evidence to the named expert or field ordered, and may specify the issues which the expert should address. Parties may instruct another expert to assist them, but any evidence from that expert will not be admissible and the costs of instructing that expert will not be recoverable from the other side.

The court may order that expert evidence is to be given by a single joint expert, namely an expert who is instructed on behalf of both parties.

Expert evidence is usually given in the form of a written report, which must be the independent product of the expert. The expert's overriding duty is to the court and not to the party that instructed him. Where separate experts are instructed by the parties, reports are usually exchanged simultaneously, but may be exchanged sequentially.

Following the simultaneous exchange of expert reports, a party may put questions to the other party's expert for the purpose of clarifying his report. Questions must normally be put within 28 days of service of the report. There is then likely to be a discussion between the experts for the purpose of reaching an agreed opinion on the issues where possible. An expert may give oral evidence at trial only with the court's permission.

Preparation for trial

The courts are reluctant to postpone a trial date or period that has been fixed without a very good reason. Therefore, although most cases settle, it is important to be properly prepared in case the matter does proceed to trial. Some of the steps required are set out below.

Pre-trial review

The court may order that a pre-trial review (PTR) be held, particularly in more substantial cases where there are significant issues between the parties. The main purposes of the PTR are to:

- Check that the parties have complied with all previous court orders and directions.

- Prepare or finalise a timetable for the conduct of the trial, including the issues to be determined and the evidence to be heard.

- Fix or confirm the trial date.

Preparation of trial bundles

Trial bundles are files of the statements of case, relevant orders and key evidence that are used by the court and the parties during the trial. Preparing the trial bundles is usually the responsibility of the claimant's solicitors but the court expects co-operation between the parties to try to agree the documents to be included. It can be a time-consuming task and requires significant planning and attention to detail.

Preparation of skeleton arguments

Each party will be required to supply the court and the other party with a written skeleton argument, namely a written outline of that party's case and arguments before trial. Skeleton arguments are usually drafted by counsel.

Trial and judgment

You should note that:

- The length of the trial will depend on the complexity of the legal and factual issues to be resolved and the number of witnesses permitted to give evidence.

- The trial will be held in public, unless the court has ordered that it may be held in private because it involves matters of a confidential nature and publicity would cause harm or damage.

- The trial will be heard by a single judge alone except in some fraud and defamation cases.

- The judgment may be given immediately after the trial but is often "reserved" to a later date, particularly in complex matters. This means that the parties would not know the judge's decision until some time after the end of the trial.

ADR, Part 36 offers and settlement

It is important to keep settlement in mind at all stages of the proceedings. The court rules and the courts encourage settlement of disputes by Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) such as by:

- Holding without prejudice meetings or discussions

- Making offers

- Attending a mediation

Although the court cannot order the parties to enter into ADR, it may impose costs penalties on a party who unreasonably refuses to participate in a form of ADR. If there are any prospects of settling, it usually better to do so sooner rather than later, to avoid further legal costs.

Making offers of settlement can be an important tactical step in litigation, as they put pressure on the other side to settle the case and, to some extent, can protect the offeror's position on costs.

Enforcement

Once judgment has been obtained, the judgment debtor should pay voluntarily any money owed under the judgment. If payment is not made, there are a number of enforcement procedures available to the judgment creditor to enforce payment.

Examples include:

- Execution against goods owned by the judgment debtor, where an enforcement officer is commanded to seize and sell a judgment debtor's goods.

- An attachment of earnings order, under which a proportion of the judgment debtor's earnings is deducted by his employer and paid to the judgment creditor until the judgment debt is paid.

- A charging order over property owned by the judgment debtor.

The appropriate procedure will depend on the circumstances, including the nature and location of the debtor's assets.

Appeals

It is open to the unsuccessful party to apply for permission to appeal a judgment or order. A decision may be appealed only on the basis that it was either wrong or unjust because of a serious procedural or other irregularity in the proceedings. The general rule is that notice of an appeal must be filed within 21 days of the judgment or order (subject to certain exceptions).

If there is an appeal, it may be necessary to apply for a stay of any order or enforcement of the judgment.

Costs

The estimated costs of the litigation can be one of the most significant factors to consider when deciding whether to pursue a case.

The general rule

The general rule regarding costs in litigation is that, if your claim succeeds, you will be entitled to recover a contribution towards your costs from the defendant. On the other hand, if the claim fails, you are likely to be required to pay a portion of the defendant's costs. It is very unusual for a party to be able to recover all of the costs incurred in the litigation. The successful party can usually only recover a contribution towards their costs.

The court’s discretion

The court has ultimate discretion to make a different costs order and how much, if anything, a party should pay. The court will take into account factors such as the conduct of the parties and any Part 36 or other admissible offers to settle the case.

Procedure for determining costs

The actual amount of costs to be paid is subject to an assessment process, unless the parties can agree the amount that will be paid.

When an Order for payment of costs is made by agreement of the parties or by the Court, the proceedings for the claim will be concluded and the procedure for recovering costs will commence.

Whilst the costs will have been incurred as a result of the claim, the procedure for recovering costs is dealt with as a separate issue if they have not been included in any global settlement. This can involve further Court proceedings to obtain a Court Order for payment of costs and/or to determine the amount to be paid by way of costs if attempts to resolve the issue of the payment of costs and the amount of costs to be paid by agreement are unsuccessful.

Court proceedings in respect of the issue of costs are known as assessment of costs. Prior to commencing Court proceedings for the assessment of costs, it will be necessary for a Bill of Costs to be drawn by a Costs Draftsman. A Bill of Costs is the formal prescribed Court format for detailing the costs incurred during the claim that are being claimed by the party who has been successful.

Summary

If this matter proceeds to litigation, there will be significant time and commitment required by you and any other individuals/organisation involved. You may be needed to assist with the preparation of your case and possibly attend court at preliminary hearings or to give evidence if the case goes to trial.